All the Storyspaces

I’m excited to share a new project that I’ve been laying the groundwork for: I’m planning to read all works published by Eastgate Systems and write about each one on the blog. Founded by hypertext maverick Mark Bernstein, Eastgate took on the Storyspace authoring system (originally developed by Jay David Bolter, John B. Smith, and Michael Joyce) and published the ‘first hypertext novel,’ Joyce’s afternoon, a story in 1990 (though Joyce had written afternoon in the mid-80s and started sharing it in 1987). Eastgate would go on to publish 30+ ‘monograph’ works of hypertext fiction, poetry, and non-fiction along with eight issues of its serial Eastgate Quarterly Review of Hypertext through the 90s and 2000s, distributing these after the fashion of small press literature to bookstores, academic libraries, and individual subscribers. Running in parallel to the development of the Web, where the next waves of electronic literature would receive far wider distribution and readership, Eastgate established the mold for the publishing of standalone works of literary software.

As Kathi Berens points out,1 though, we should be suspect of this widely accepted narrative of the development of electronic literature, which smacks of a Great Men of Literature story that’s all too common across eras of literary history. For instance, Berens discusses how Judy Malloy’s Uncle Roger gets overlooked, a work of hypertext fiction originally published to the Well in 1986 that predates Storyspace and afternoon. Malloy would author several Eastgate works, including its name was Penelope, Forward Anywhere (co-authored with Cathy Marshall), and l0ve0ne, a web-based hypertext from the Eastgate Web Workshop, though these are not as prominently discussed in the literature on Eastgate as afternoon has been. In addition to Bernstein’s work, Diane Greco served as the long-time editor of Eastgate titles and authored her own work Cyborg: Engineering the Body Electric. Astrid Ensslin, in her excellent recent book on the Eastgate Quartely Review,2 spotlights Greco as integral to Eastgate’s publishing efforts, though Greco’s contributions have been little discussed to date.

One of the things I hope to accomplish by reading all of the Eastgate titles, including works that were not released on physical media like l0ve0ne, is to develop a more complicated sense of this era of early electronic literature. While I’ve read the couple hugely influential works written with Storyspace and published by Eastgate — the aforementioned afternoon and Shelley Jackson’s Patchwork Girl — and only cursorily explored a few other titles, this is just a sliver of the catalog. Just going through the disks, looking at the packaging and popping some in to try them out, suggests that there are some interesting and striking works written by authors experimenting with a standalone hypertext system. There are things here deserving of much more attention.

Side note: In addition to this one example, there are many precursors to the works of hypertext literature published by Eastgate — such as Mindwheel, an Electronic Novel written by US poet laureate Robert Pinsky — and I hope to read and write about these on the blog as well.

I’ve been inspired by recent efforts to play through the entirety of the Infocom catalog — Kay Savetz and Carrington Vanston successfully podcasted their way through all the Infocom games on Eaten by a Grue, and Drew Cook &co are currently blogging and podcasting through this same catalog at the Gold Machine. The project of reading and discussing all of the Eastgates is similar in scope to all of the Infocoms: both publishers put out around 30+ titles, and both publishers were especially active over the span of about a decade. (I’ve already discussed my own readthroughs of some Infocom classics on the blog, and I’ll probably pepper in more of those in the future, too). The project is big but doable, and there’s something to be gained — I hope! — from taking this cross-cut view of the whole corpus, a perspective earned not from distant reading but rather from close and persistent reading.

The other major inspiration and motivation for this project is the ongoing work of Dene Grigar and the Electronic Literature Lab. Grigar &co have been documenting early electronic literature, focusing on the Eastgate School and their contemporaries, through a number of initiatives over the years. Along with Stuart Moulthrop, author of the Eastgate title Victory Garden, Grigar and the ELL team have been conducting “traversals” of early electronic literature works. As Moulthrop and Grigar explain, a traversal is a “reflective encounter with a digital text in which the possibilities of that text are explored in a way that indicates its key features, capabilities, and themes.”3 In practice, these traversals involve recording a reading of the work, often by the author of the work itself, and interacting with the work in the original computing environment that was used to read the work when it was first published. The sort of ‘think aloud protocol’ that accompanies the readings elicit insightful commentary by the author (or in some cases an informed reader) that helps to illustrate the importance of the work.

These traversals, and the related documentation, notes, and critical essays published in the ongoing series of Rebooting Electronic Literature books, are invaluable resources for understanding this era of 90s and early 2000s electronic literature. But the preservation of literature — and the traversal project suggests — cannot only consist of documentation; it must also consist of readerly engagement. Literature is made to be read, and it is preserved through the continued engagement of new readers. While the traversals seek to capture this early electronic literature in something approaching its initial context, my project will be concerned more with tracking the reading of these works from the perspective of a contemporary reader. What does it mean to read historical works of electronic literature from the late ’80s, ’90s, and early ’00s — works that are dependent on obsolete but still widely available hardware and software — today, in the 2020s?

On that last point, how I have built up my personal library of Eastgate titles and the equipment needed to read them is instructive. In Pathfinders, the first scholarly book generated from the ELL’s preservation efforts, Grigar lists 33 ‘monograph’ titles published by Eastgate, starting with The Election of 1912 by Mark Bernstein and Erin Sweeney from 1988 through to Those Trojan Girls by Mark Bernstein from 2016.4 Most, but not all of these 33 titles (and the eight issues of EQRH) remain available for purchase from Eastgate. I know because I (well, really the amazing UNCG LIS admin assistant) placed an order for the entirety of Eastgate’s back catalog. Some of the works are no longer “in print,” and not even actively listed on Eastgate’s website, and the rights for some of the works that are still listed for sale have reverted back to the authors, so these are effectively “out of print” as well. I was able to receive copies of most of Eastgate’s back catalog and, supplemented by eBay, now hold a collection of 37 titles.

Of the few works that I have not yet been able to track down, a couple of these have been migrated to the Web, and disks also reside in the Rubenstein Library at Duke. If I’m not able to eventually track down copies of these works, I’ll likely visit Duke and also consult the web versions. I’ll also have more on how Eastgate titles have been collected in libraries in a later post…

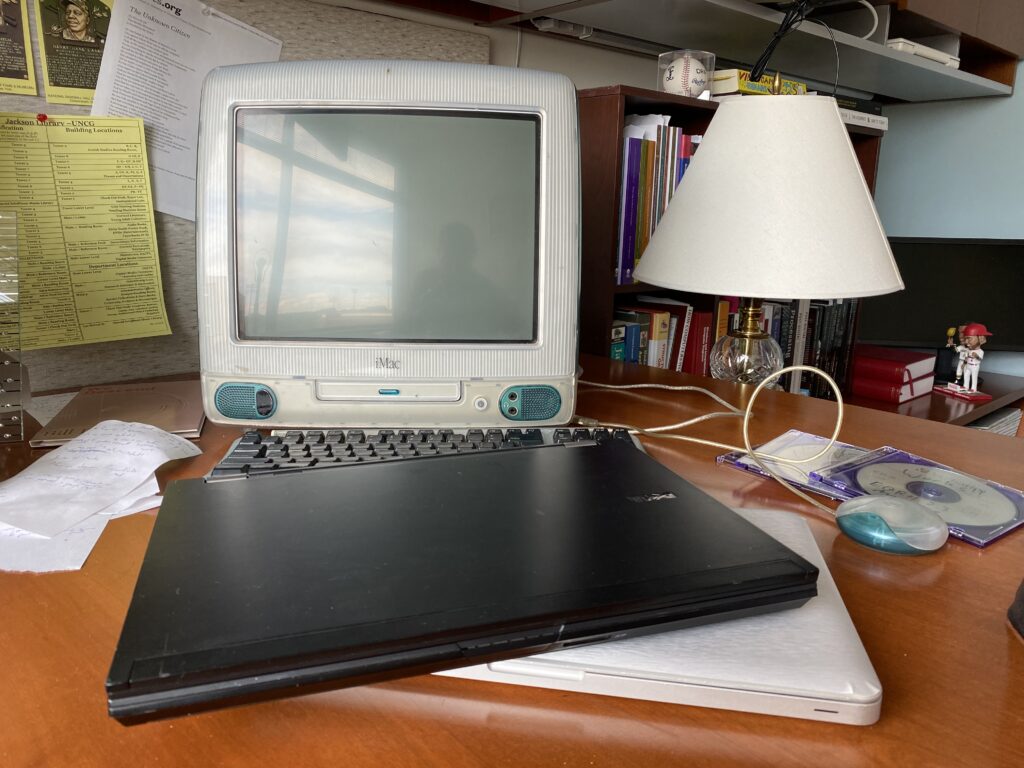

The other complicating factor is that essentially none of the works, even those still available for purchase, can run on current computers. The vast majority of the works need to be run within a 32-bit Windows operating system or a classic Mac operating system (9.x or earlier). A select few works have been re-released on USB sticks, but even these are only compatible with older versions of Mac OSX (e.g. High Sierra). So in order to read through the entirety of the catalog, I’ve needed to acquire some old computers.

Again, eBay proves essential for homegrown digital preservation efforts, as I was able to find the three relatively inexpensive machines that I’ll need for my read through of every Eastgate title: an iMac G3, a Dell laptop running Windows XP, and a MacBook Pro running High Sierra (only necessary to read Those Trojan Girls, though this is also needed to run the latest version of the Storyspace authoring software). I’ll likely get into more details about the quirks and tricks needed to read the Eastgate titles on these different machines, as well as some differences across interacting with Storyspace across these different computing environments, in my posts on specific works.

I will note here, though, that this cobbled together approach is different in important ways from the traversals done at the ELL. While the purpose of the traversals is authenticity to the ‘original’ way in which these works were initially created and experienced, I’m ultimately less concerned with carefully maintaining the original context of the works, and more interested in how workarounds and patched together solutions can make these works readable with some minimal (but not insignificant) financial and technological investment. We can read a copy of the first edition of Frankenstein, carefully preserved in a special collections library, and we can read the Penguin Classics paperback, picked up used for a buck. Of course these are drastically different experiences, and we’ll get very different things from each text — but these both constitute a reading of the work. Literature has always been malleable, fitting into whatever containers will hold it, and we need to develop this same sensibility for electronic literature as well. The ‘special collections’ experience of e-lit is necessary, but so too is the picked up cheap and used experience. For Eastgate titles — and other pre- and extra-web hypertexts — we don’t have a model or framework for the cheap’n’used experience. That’s also part of what I’m hoping to chart out in this project.

As part of this project, I’m working with a UNCG LIS Graduate Assistant to do an extensive literature search for everything we can find written about Eastgate titles, including academic articles but also informal writing by authors and critics online — reviews, blog posts, a blurb on an author’s website. I am planning to use these primary and secondary sources to do more in-depth research as I write scholarly pieces to be published in academic venues, but I’m sure some of that will get brought in here on the blog as well.

As I’ve already alluded to in this post, I’m not planning to make this reading of Eastgate’s back catalog the sole focus of the blog or my scholarly research. I plan to continue to read recent and historical works of electronic literature across various genres and formats as I do this Eastgate read through. It will realistically take me several years to get through the entirety of the Eastgate catalog, and I don’t want to exclusively dwell in 90s hypertext for that long, as much as I have a fondness for it. I’m interested to see what connections I can draw not only among works in the Eastgate catalog, but also across different types of electronic literature, especially contemporary stuff.

I don’t know where this reading will take me, but I’ve been grasping for a structure to focus this next phase of my research agenda. I think this will do.

References

- Kathi Inman Berens, “Judy Malloy’s Seat at the (Database) Table: A Feminist Reception History of Early Hypertext Literature,” Literary and Linguistic Computing 29, no. 3 (September 1, 2014): 340–48, https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqu037.

- Astrid Ensslin, Pre-Web Digital Publishing and the Lore of Electronic Literature, Elements in Publishing and Book Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022).

- Stuart Moulthrop and Dene Grigar, Traversals: The Use of Preservation for Early Electronic Writing (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2017), 7.

- Stuart Moulthrop and Dene Grigar, Pathfinders: Documenting the Experience of Early Digital Literature (Vancouver, WA: Nouspace Publications, 2015), https://scalar.usc.edu/works/pathfinders/the-electronic-literature-collection?path=introduction.