Descending, rendering

I started my read-through of the Eastgate back catalog with We Descend: Archives Pertaining to Egderus Scriptor, Volume 1 by Bill Bly, originally released in 1997 on floppy disk for Mac (compatible with Storyspace 1, on Mac OS 9 and earlier). I have copies of two later re-releases: the CD-ROM version, first produced in 2006 (compatible with Storyspace 2, on 32-bit Windows operating systems or Mac OS X 10.4 and earlier) and the USB-drive version (not sure when this was first produced, but it’s compatible with Storyspace 3 on Mac OS X 10.5 and later). Robert Kendall also featured an excerpt of We Descend, translated into HTML, on his site Word Circuits, as part of a Gallery of hypertext poetry and fiction. As Bly relates in the interview conducted in the Pathfinders project,1 he actually began writing this piece on bits and scraps of paper in the mid-80s, many years before he was aware of hypertext, starting after a phrase popped into his head: “If this document is authentic.”

We Descend presents itself as ‘an archives,’ a “hodgepodge of documents whose only commonality, in some cases, is that they have ended up in the same place” (“Foreward”). The reader navigates and inspects the documents, puzzling through fragmented writings from disparate authors, descending through strata of imagined histories, never quite sure how these lexia fit together. I was compelled to start my Eastgate read-through with this work for this very reason; I’m interested in thinking about the representation of archival work in electronic literature, how reading and writing e-lit requires a certain archival/curatorial mindset, and how archival concepts like provenance and authenticity can be applied in the scholarly interpretation of e-lit.

For We Descend, this is both a work about archives and the byproduct of Bly’s writerly archives. The structure and content of the published work mirrors the variegated production process, reflecting the many analog and digital writing technologies that have shaped the composition and the various publications of the work. This curious (and sometimes frustrating) structure is cued to the reader from the byline found on the cover of the work: rendered into hypertext…by Bill Bly. Bly takes the detached stance of a translator or a curator rather than the author of the work. He’s the latest in a series of people to encounter this cache of documents, which he now hands off to the reader.

Upon opening the work, the reader can take a look at the Directions, which actually constitutes some incredibly helpful documentation for navigating Storyspace texts (e.g. providing tips for how to reveal links hidden in a lexia, the utility of the different schematic views that Storyspace offers to readers). Perhaps a product of it being an early example of a commercial hypertext reading and writing environment, Storyspace has a pretty steep learning curve. It’s easy enough to open a text and begin clicking around, but there are a number of tools available for navigating texts, such as providing different views of the work’s structure and means for tracking links in and out of different lexia, that are left for the reader to discover and teach themselves. Some of this is covered in the paper manual that comes enclosed inside the work’s packaging, but Bly offers a far more detailed overview for readers new to Storyspace and hypertext in general, like he himself was during the composition process for We Descend.

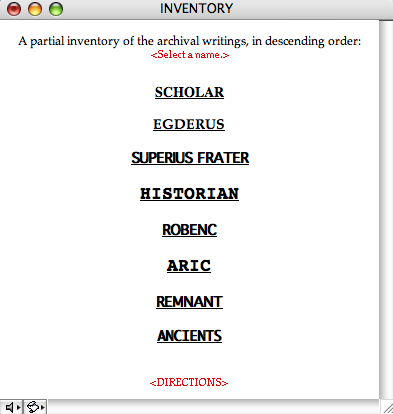

Bly further eases readers into the navigation of this work by creating a preset ‘default’ path through the archives (clicking Just Start from the title page). The default reading serves to introduce readers to these main characters and orient them to the contours of a plot—though a concrete sense of the multiple narratives contained in We Descend remains elusive even at the conclusion of this default path. Bly constructs a second way to interact with the work, via an Inventory of the main characters, which takes the reader to a selected portion of writings relevant to that character.

In broad strokes, there are four main strata of materials, each with its own issues and tensions: 1) the Scholar, who has found a cache of documents of dubious authenticity, though, if authentic, these documents threaten to upset the prevailing understanding of a past era; 2) Egderus, a scribe in a monastic house in a vaguely medieval setting, who negotiates personal and political ordeals that result from the discovery of documents that threaten to upset the prevailing understanding of a past era (see the repetition!); 3) the Ancients, a set of writings recovered from a lost historical period that disturb later periods’ understandings of this pre-history; and 4) the Remnant, a collection of koan-like sayings, reminiscent of mythico-religious writings like those of the Desert Fathers that seem to exist almost out of time. The reader, perhaps along with Bly, represent a fifth stratum, the latest to encounter this accumulating stack of documents.

One of the key themes, thus, is the power of how we interpret the past—mediated through our encounters with the fragmented documentary remains of preceding cultures—for shaping our lives in the present. The stakes differ markedly: the Scholar weighs the impacts of his interpretation of these documents on his career, while Egderus deals with the political violence leveled to quell a perceived heresy. But, across these strata, it is the obstinacy of archival silences, the dumbness of documents that need to be interpreted and enacted, which creates a space for the exertion of power in the present—to insist that the past was otherwise. This theme is wonderfully framed in a lexia that comes early on in the default path: “our idea of that era is based upon the fact that the only writings we have are lists, inventories, and fragments of what might be poetry, or might merely be descriptions of exotic objects belonging to now-lost inventories (“/….If this document is”). What we take in the present as poetry could just be lists and inventories, the byproducts of bureaucratic processes that we’re misreading as artful. This brings to mind conceptual poets like Robert Fitterman, specifically his work Metropolis that consists of artful misreading of advertisements, junk language. The poetry that Bly is gesturing at, even if the original context of what we now read as artful is ultimately mundane, comes in how these documents pass through time, the ability of a mundane document to transport someone in the present to a material moment from the past, however obscured that view may be.

The work contains interesting traces of its own history as well: traces of how Bly has shaped this text across technologies of writing, from longhand to hypertext, and traces of how versions of this work have migrated across different operating systems. Along with an essay that Bly wrote for Judy Malloy’s excellent site “Authoring Software,”2 the Pathfinders interview referenced above provides great insight into how Bly adapted a project that he started by compiling notes on scraps of paper to the Storyspace environment. In translating long passages written in hand to shorter, interlinked lexia in hypertext, Bly used the ‘explode’ feature in Storyspace, which takes long blocks of text and then breaks them into smaller pieces linked in a linear sequence. While lexia in Storyspace will often have many ‘word that yield’ (i.e. significant words that link to other lexia), offering many potential paths for the reader, this ‘explode’ feature creates stretches of short lexia that the reader follows in a predetermined sequence — at the end of a lexia, hit return, and proceed to the next lexia in the sequence. Bly also mixes in tangential and substantial alternative routes to follow, but significant stretches of We Descend consist of these long passages that have been exploded into shorter, linearly-sequenced lexia: pages paper-clipped together by the curator into coherent micro-narratives within a larger, less obviously coherent mess of an archives.

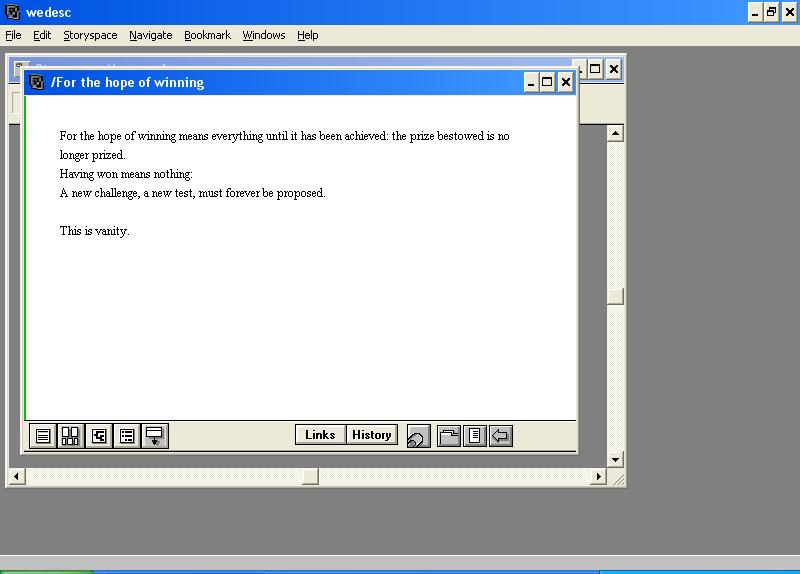

I caught onto this structure on my initial reading, though in the Pathfinders interview, Bly points out a trace of the ‘explode’ feature left on the text. In Storyspace, authors can label each lexia, typically the first few words of the passage. When a longer passage has been exploded into smaller lexia, Storyspace labels each newly generated lexia following this convention, though inserting a backslash to the start of the label. See this example featuring a lexia (“/For the hope of winning”) from a series of passages that recount sayings of the Remnants, mentioned above:

This little tick mark is easy to overlook, though it serves as a meaningful indication of the structure of the text. This lexia is one in a linear sequence, strung together (after having been exploded apart) — a mark of the curator’s work.

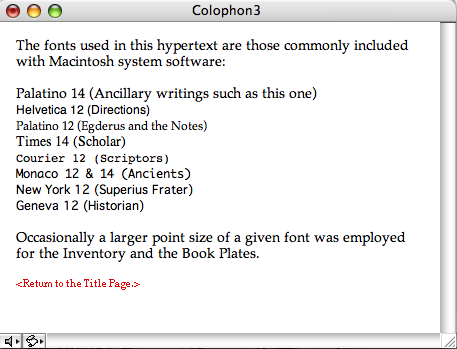

The fonts encountered across the lexia provide another important trace of how We Descend has been shaped by the technologies used to compose the work. As Bly notes in his introductory instructions for readers, “a number of adjustments were made [for the Windows version] to accomodate (sic) the divergent ways in which fonts and colors are handled by the different operating systems” (“The fonts used in this”). A further lexia (“Colophon 3”) enumerates the various fonts that are used in the Mac version of the work; comparing this lexia across the Mac OS X 10.4 and Windows XP versions of the work immediately demonstrates the significance of change in operating system environment.

The fonts are used to visually differentiate the many voices — and, in turn, the distinct temporal strata — that populate the work. When reading the Storyspace 2 version of the text on a compatible Mac machine, there are 7 different fonts used, several of them (like Monaco) proprietary to Apple. To my eye, the Windows rendering of the text reduces this to 2 different fonts (Palatino and Times) in varying size. Extending the metaphor of sifting through archival documents, these distinguishing fonts stand in for characteristics of documents like handwriting or type of paper that might provide evidence as to the provenance or author.

The impact of these varying fonts is made even more clear when reading the text, starting from the Inventory that indexes the different creators whose materials are included in the archives.

While I haven’t been able to find anything from Bly about his intention in choosing particular fonts for particular voices, some characteristics of typeface seem to indicate things about the speaker. For instance, the switch between serif (Palatino, Times) and sans-serif (Geneva, Monaco) fonts seem to indicate differences in perspective. Writings by Egderus and the Superius Frater are both in serif fonts, and both of these speakers are, to an extent, supporting and advancing the perceived view of history, working within the existing social structure and ideology based in that view of history (even if neither is fully comfortable with this). In contrast, the writings of the Historian and the Ancients are in sans-serif fonts; both of these bodies of writings represent direct attacks, departures from, or criticisms of the perceived view of history. Notably, all of the fonts used in the Windows version have serif typefaces, totally eliminating this potential interpretation of the work.

These differences are not totally lost in the Windows rendering of the text, as other context clues make it possible to discern changes in voice and perspective, but something is definitely missing when that change in perspective isn’t signaled at the level of the typeface — especially when going through the ‘default’ reading of the text, which ranges across all the various voices and doesn’t explicitly signal shifts in speaker or time period. Reading through the default path in the Mac version is truly a different experience, with the subtle but noticeable shifts in typeface enacting these shifts in voice, temporal orientation, and perspective. For instance, this sequence at the beginning of the default path is the first such major shift:

The voice of one of the Ancients, describing the experience of living through some catastrophe, surviving some apocalypse that has sundered a connection to a rich civilization, gives way to the anxious, skeptical voice of the Scholar. Again, this shift in font, visible to the eye before the reader engages with the content of the lexia, enacts the experience of diving into the archives, crossing strata of media, and thus historical context.

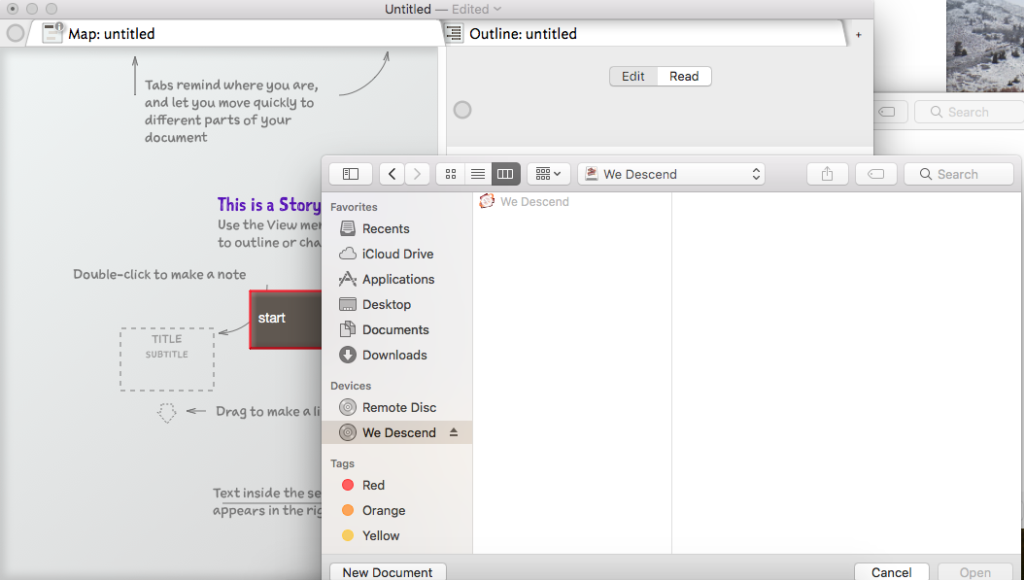

Curiously, these different fonts are not supported in the latest re-release for Mac machines running current macOS (10.5 and later). After I noticed this difference in the fonts between the older Mac version and the Windows XP version, I fired up the latest re-release of We Descend on a MacBook running macOS High Sierra…and it looked closer to the Windows XP version of the text:

This is puzzling since the various fonts used are all still included as defaults in current Mac operating systems. My best guess is that something about how these fonts are rendered or recognized was lost in the migration from Storyspace 2 to Storyspace 3. As described on Eastgate’s page for the current release of the Storyspace software, Storyspace 3 is designed to be compatible with Tinderbox, Eastgate’s other major piece of hypertext software. The few Eastgate works that have been re-released for Storyspace 3 (We Descend, afternoon, Victory Garden, and Patchwork Girl, I believe are the extent) have essentially been migrated to a new file format that’s compatible with Tinderbox. While the Eastgate page linked above claims that “Storyspace 3 works with existing Storyspace files and creates new Storyspace documents in a robust, state-of-the-art XML format. Legacy Storyspace work immediately takes advantage of Storyspace 3’s outstanding new typography.” This has not been true in my experience at least, as I have not been able to successfully open SSP2 files using Storyspace 3 at all, let alone to take advantage of this outstanding new typography…

The different fonts are not essential for a meaningful reading of We Descend — I actually read through the work initially via the Windows XP version and was able to piece together the different voices without too much trouble — but these variable fonts are integral to a particular reading, we could even say the ‘authorized’ or intended reading, of the text. The archives of this work has proliferated across many different computing environments, with editions published across for all three releases of Storyspace for both Mac and Windows, in addition to excerpts migrated to HTML and published to the Web, but only a couple of these instantiations of the work (the original Storyspace 1 release for Mac and the later SSP2 re-release for Mac) actually renders this ‘authorized’ version of the text.

That said, We Descend seems to encourage a proliferation that begets transformation. Bly has been an active agent in this proliferation, porting the project to every hypertext reading/writing tool he’s been able to get his hands on. This exploration and adaptation has continued as Bly has ‘rendered’ two further volumes of the Archives pertaining to Egderus Scriptor, at one point bending/breaking Volume 2 into a WordPress site.3 Fortunately, both volumes 2 and 3 are now much more readable as straightahead webpages (published and hosted by The New River journal of digital art and literature),4 no longer contorted into the shape of a blog. So there may only be a few ways to ‘authentically’ read We Descend in the shape and form that Bly originally intended, but we should never hold an author to their original intentions for all time. The text moves; the archives accumulates new documents. And every document is one that begs to be read, regardless of its history, or its path of production—even if it may not be ‘authentic.’

References

- Stuart Moulthrop and Dene Grigar, Pathfinders: Documenting the Experience of Early Digital Literature (Vancouver, WA: Nouspace Publications, 2015), https://scalar.usc.edu/works/pathfinders/bill-bly.

- Bill Bly, “Authoring Software – Process – Bill Bly,” Content | Code | Process: Authoring Electronic Literature (blog), accessed November 10, 2022, https://www.narrabase.net/bill_bly.html.

- https://web.archive.org/web/20160821111546/http://www.wedescend.com/defaultpath/

- http://www.wedescend.net/